Bonus Army

| Bonus Army | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Bonus Army marchers (left) clash with the police (right) | |||

| Date | July 28, 1932 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Impoverishment of World War I veterans due to the Great Depression | ||

| Resulted in | Demonstrators dispersed, demands rejected, Herbert Hoover loses 1932 presidential election | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

Walter W. Waters | |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

The Bonus Army was a group of 43,000 demonstrators – 17,000 veterans of U.S. involvement in World War I, their families, and affiliated groups – who gathered in Washington, D.C., in mid-1932 to demand early cash redemption of their service bonus certificates. Organizers called the demonstrators the Bonus Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.), to echo the name of World War I's American Expeditionary Forces, while the media referred to them as the "Bonus Army" or "Bonus Marchers". The demonstrators were led by Walter W. Waters, a former sergeant.

Many of the war veterans had been out of work since the beginning of the Great Depression. The World War Adjusted Compensation Act of 1924 had awarded them bonuses in the form of certificates they could not redeem until 1945. Each certificate, issued to a qualified veteran soldier, bore a face value equal to the soldier's promised payment with compound interest. The principal demand of the Bonus Army was the immediate cash payment of their certificates.

On July 28, 1932, U.S. Attorney General William D. Mitchell ordered the veterans removed from all government property. Washington police met with resistance, shot at the protestors, and two veterans were wounded and later died. President Herbert Hoover then ordered the U.S. Army to clear the marchers' campsite. Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur commanded a contingent of infantry and cavalry, supported by six tanks. The Bonus Army marchers with their wives and children were driven out, and their shelters and belongings burned.

A second, smaller Bonus March in 1933 at the start of the Roosevelt administration was defused in May with an offer of jobs with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) at Fort Hunt, Virginia, which most of the group accepted. Those who chose not to work for the CCC by the May 22 deadline were given transportation home.[2] In 1936, Congress overrode President Roosevelt's veto and paid the veterans their bonus nine years early.

Origin of military bonuses

[edit]

The practice of war-time military bonuses began in 1776, as payment for the difference between what a soldier earned and what he could have earned had he not enlisted. The practice derived from English legislation passed in the 1592–93 session of Parliament to provide medical care and maintenance for disabled veterans and bonuses for serving soldiers.

In August 1776, Congress adopted the first national pension law providing half pay for life for disabled veterans. Considerable pressure was applied to expand benefits to match the British system for serving soldiers and sailors but had little support from the colonial government until mass desertions at Valley Forge that threatened the existence of the Continental Army led George Washington to become a strong advocate.

In 1781, most of the Continental Army was demobilized. Two years later, hundreds of Pennsylvania war veterans marched on Philadelphia, then the nation's capital, surrounded the State House, where the U.S. Congress was in session, and demanded back pay. Congress fled to Princeton, New Jersey, and several weeks later, the U.S. Army expelled the war veterans from Philadelphia.[citation needed] Congress progressively passed legislation from 1788 covering pensions and bonuses, eventually extending eligibility to widows in 1836.[3]

Before World War I, the soldiers' military service bonus (adjusted for rank) was land and money; a Continental Army private received 100 acres (40 ha) and $80.00 (2017: $1,968.51) at war's end, while a major general received 1,100 acres (450 ha). In 1855, Congress increased the land-grant minimum to 160 acres (65 ha), and reduced the eligibility requirements to fourteen days of military service or one battle; moreover, the bonus also applied to veterans of any Indian war. The provision of land eventually became a major political issue, particularly in Tennessee where almost 40% of arable land had been given to veterans as part of their bonus. By 1860, 73,500,000 acres (29,700,000 ha) had been issued and lack of available arable land led to the program's abandonment and replacement with a cash-only system.[citation needed] Breaking with tradition, the veterans of the Spanish–American War did not receive a bonus and after World War I, that became a political matter when they received only a $60 bonus ($1,050 in 2024).[4] The American Legion, created in 1919, led a political movement for an additional bonus.[5]

On May 15, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge vetoed a bill granting bonuses to veterans of World War I, saying: "patriotism... bought and paid for is not patriotism." However, the Bonus Bill was endorsed by Henry Cabot Lodge and Charles Curtis. Congress overrode Coolidge's veto of the Bonus Bill, enacting the World War Adjusted Compensation Act.[6] Each veteran was to receive a dollar for each day of domestic service, up to a maximum of $500 (equivalent to $8,900 in 2023), and $1.25 for each day of overseas service, up to a maximum of $625 ($11,110 in 2024).[7] Deducted from this was $60, for the $60 they received upon discharge. Amounts of $50 or less were immediately paid. All other amounts were issued as Certificates of Service maturing in 20 years.[8]

There were 3,662,374 Adjusted Service Certificates issued, with a combined face value of $3.64 billion (equivalent to $65 billion in 2023).[9] Congress established a trust fund to receive 20 annual payments of $112 million that, with interest, would finance the 1945 disbursement of the $3.638 billion for the veterans. Meanwhile, veterans could borrow up to 22.5% of the certificate's face value from the fund; but in 1931, because of the Great Depression, Congress increased the maximum value of such loans to 50% of the certificate's face value.[10] Although there was congressional support for the immediate redemption of the military service certificates, Hoover and Republican congressmen opposed such action and reasoned that the government would have to increase taxes to cover the costs of the payout and so any potential economic recovery would be slowed.[11]

The Veterans of Foreign Wars continued to press the federal government to allow the early redemption of military service certificates.[12]

In January 1932, a march of 25,000 unemployed Pennsylvanians, dubbed "Cox's Army", had marched on Washington, D.C., the largest demonstration to date in the nation's capital, setting a precedent for future marches by the unemployed.[13]

Campsite

[edit]

Most of the Bonus Army (Bonus Expeditionary Force or BEF) camped in a form of a "Hooverville" on the Anacostia Flats (now Section C of Anacostia Park), a swampy, muddy area away from the federal core of Washington. Other veterans lived much closer, in partially demolished buildings on Pennsylvania Avenue near the Third Street SW.[14][15] Although occupation of Anacostia Flats was against federal law, Glassford obtained permission off the record from his friend Major General Ulysses S. Grant III, Director of Public Buildings and Public Parks in the Capital, who promised to make no objection.[16] The chosen site was located in the historically African American side of Anacostia; nearby were tennis courts and a baseball diamond, the latter of which was used by children of the camp.[17] The War Department had refused a request by Senator James Hamilton Lewis to set up billets, so veterans, women and children lived in the shelters they built from materials dragged out of a junk pile nearby, which included old lumber, packing boxes, and scrap tin covered with roofs of thatched straw.[18] The shack city was nicknamed Camp Marks, after the friendly Police Captain S.J. Marks.

Camp Marks was tightly controlled by the veterans, who laid out streets, built sanitation facilities, set up an internal police force and held daily parades. A vibrant community arose revolving around several key sections, including the religious tent, where marchers could be heard expressing forbearance, trust in God and gratitude for what they had compared to other victims of the Depression. Also popular was the Salvation Army lending library, where marchers wrote letters home in its makeshift post office (postage stamps were more prized than cigarettes, it was said).[19] To live in the camps, veterans were required to register and to prove they had been honorably discharged or provided a bonus certificate, at which point a membership card would be issued.[16] The Superintendent of the D.C. Police, Pelham D. Glassford, worked with camp leaders to supply the camp with food and supplies.

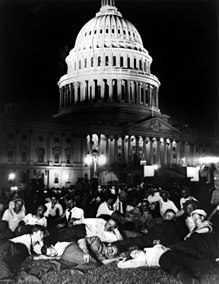

On June 15, 1932, the US House of Representatives passed the Wright Patman Bonus Bill (by a vote of 211–176) to move forward the date for World War I veterans to receive their cash bonus.[20] Over 6,000 bonus marchers massed at the U.S. Capitol on June 17 as the U.S. Senate voted on the Bonus Bill. The bill was defeated by a vote of 62–18.[21]

Police shooting

[edit]

On July 28, under prodding from President Herbert Hoover, the D.C. Commissioners ordered Pelham D. Glassford to clear their buildings, rather than letting the protesters drift away as he had previously recommended. When the veterans rioted, an officer (George Shinault) drew his revolver and shot at the veterans, two of whom, William Hushka and Eric Carlson, died later.[22][1]

- William Hushka (1895–1932) was an immigrant to the United States from Lithuania. When the US entered World War I in 1917, he sold his butcher shop in St. Louis, and joined the army. After the war, he lived in Chicago.[1] He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery a week after being shot and killed by police.[23][24]

- Eric Carlson (1894–1932) was a veteran from Oakland, California, who fought in the trenches of France in World War I.[1][25][26] He was interred in Arlington National Cemetery.[27]

During a previous riot, the Commissioners asked the White House for federal troops. Hoover passed the request to Secretary of War Patrick J. Hurley, who told MacArthur to take action to disperse the protesters. Towards the late afternoon, cavalry, infantry, tanks and machine guns pushed the "Bonusers" out of Washington.[28]

Reports on communist elements

[edit]An Army intelligence report claimed that the BEF intended to occupy the Capitol permanently and instigate fighting, as a signal for communist uprisings in all major cities. It also conjectured that at least part of the Marine Corps garrison in Washington would side with the revolutionaries, hence Marine units eight blocks from the Capitol were never called upon. The report of July 5, 1932, by Conrad H. Lanza in upstate New York was not declassified until 1991.[29]

The Department of Justice released an investigative report on the Bonus Army in September 1932, noting that communists had attempted to involve themselves with the Bonus Army from the start, and had been arrested for various offenses during protests:

- As soon as the bonus march was initiated, and as early as May, 1932, the Communist party undertook an organized campaign to foment the movement, and induced radicals to join the marchers to Washington. As early as the edition of May 31, 1932, the Daily Worker, a publication which is the central organ of the Communist party in the United States, urged worker veteran delegations to go to Washington on June 8th.[30]

In 1932, Hoover stated that the bulk of Bonus Army members behaved reasonably and a minority of what he described as communists and career criminals were responsible for most of the unrest associated with the events: "I wish to state emphatically that the extraordinary proportion of criminal, Communist, and nonveteran elements amongst the marchers as shown by this report, should not be taken to reflect upon the many thousands of honest, law-abiding men who came to Washington with full right of presentation of their views to the Congress. This better element and their leaders acted at all times to restrain crime and violence, but after the adjournment of Congress a large portion of them returned to their homes and gradually these better elements lost control."[30] In his 1952 memoir, Hoover stated that at least 900 of the Bonus Army were "ex-convicts and Communists."[31]

In his memoir The Whole of Their Lives (1948) Benjamin Gitlow of the Communist Party USA reported that a number of communists had joined the Bonus Army during their trek across the nation, with the goal of recruiting people to the communist cause.[32]

A 2009 Encyclopedia Britannica blog post asserted these would-be communist organizers were largely rejected by the Bonus Army marchers: "[T]here were communists present in the camps, led by John T. Pace from Michigan. But if Pace believed that Bonus Army was a ready-made revolutionary cadre, he was mistaken. The marchers routinely expelled avowed communists from the camps. They destroyed communist leaflets and other literature. And among their other slogans the veterans adopted a motto directed at the communists, 'Eyes front—not left!'"[33]

Army intervention

[edit]At 1:40 pm, General Douglas MacArthur ordered General Perry L. Miles to assemble troops on the Ellipse immediately south of the White House. Within the hour the 3rd Cavalry led by George S. Patton, then a Major, crossed the Memorial Bridge, with the 12th Infantry arriving by steamer about an hour later. At 4 pm, Miles told MacArthur that the troops were ready, and MacArthur (like Eisenhower, by now in service uniform) said that Hoover wanted him to "be on hand as things progressed, so that he could issue necessary instructions on the ground" and "take the rap if there should be any unfavorable or critical repercussions."[34]

At 4:45 pm, commanded by MacArthur, the 12th Infantry Regiment, Fort Howard, Maryland, and the 3rd Cavalry Regiment, supported by five M1917 light tanks commanded by Patton, formed in Pennsylvania Avenue while thousands of civil service employees left work to line the street and watch. The Bonus Marchers, believing the troops were marching in their honor, cheered the troops until Patton ordered the cavalry to charge them.[35]

After the cavalry charged, the infantry, with fixed bayonets and tear gas (adamsite, an arsenical vomiting agent) entered the camps, evicting veterans, families, and camp followers. No shots were fired. The veterans fled across the Anacostia River to their largest camp, and Hoover ordered the assault stopped. MacArthur chose to ignore the president and ordered a new attack, claiming that the Bonus March was an attempt to overthrow the US government. 55 veterans were injured and 135 arrested.[1] A veteran's wife miscarried. When 12-week-old Bernard Meyer died in the hospital after being caught in the tear gas attack, a government investigation reported he died of enteritis, and a hospital spokesman said the tear gas "didn't do it any good."[36]

During the military operation, Major Dwight D. Eisenhower, served as one of MacArthur's junior aides.[37] Believing it wrong for the Army's highest-ranking officer to lead an action against fellow American war veterans, he strongly advised MacArthur against taking any public role: "I told that dumb son-of-a-bitch not to go down there," he said later. "I told him it was no place for the Chief of Staff."[38] Despite his misgivings, Eisenhower wrote the Army's official incident report that endorsed MacArthur's conduct.[39]

Although the troops were ready, Hoover twice sent instructions to MacArthur not to cross the Anacostia bridge that night, both of which were received. Shortly after 9 pm, MacArthur ordered Miles to cross the bridge and evict the Bonus Army from its encampment in Anacostia.[40] This refusal to follow orders was claimed by MacArthur's assistant chief of staff George Van Horn Moseley. However, MacArthur's aide Dwight Eisenhower, Assistant Secretary of War for Air F. Trubee Davison, and Brigadier General Perry Miles, who commanded the ground forces, all disputed Moseley's claim. They said the two orders were never delivered to MacArthur and they blamed Moseley for refusing to deliver the orders to MacArthur for unknown reasons.[41][42] The shacks in the Anacostia Camp were then set on fire, although who set them on fire is somewhat unclear.

Aftermath

[edit]Joe Angelo, a decorated hero from the war who had saved Patton's life during the Meuse-Argonne offensive on September 26, 1918, approached him the day after to sway him. Patton, however, dismissed him quickly. This episode was said to represent the proverbial essence of the Bonus Army, each man the face of each side: Angelo the dejected loyal soldier; Patton the unmoved government official unconcerned with past loyalties.[43]

Though the Bonus Army incident did not derail the careers of the military officers involved, it proved politically disastrous for Hoover, and it was a contributing factor to his losing the 1932 election in a landslide to Franklin D. Roosevelt.[44]

Police Superintendent Glassford was not pleased with the decision to have the Army intervene, believing that the police could have handled the situation. He soon resigned as superintendent.

MGM released the movie Gabriel Over the White House in March 1933, the month Roosevelt was sworn in as president. Produced by William Randolph Hearst's Cosmopolitan Pictures, it depicted a fictitious President Hammond who, in the film's opening scenes, refuses to deploy the military against a march of the unemployed and instead creates an "Army of Construction" to work on public works projects until the economy recovers.[citation needed] First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt judged the movie's treatment of veterans superior to Hoover's.[45]

During the presidential campaign of 1932, Roosevelt had opposed the veterans' bonus demands.[46] He became President in March, 1933, and soon a second bonus march was planned for May by the "National Liaison Committee of Washington." It demanded that the Federal government provide marchers housing and food during their stay in the capital.[47] Despite his opposition to the marchers' demand for immediate payment of the bonus, Roosevelt greeted them quite differently than Hoover had done. The Roosevelt administration set up a special camp for the marchers at Fort Hunt, Virginia, providing forty field kitchens serving three meals a day, bus transportation to and from the capital, and entertainment in the form of military bands.[48]

Administration officials, led by presidential confidant Louis Howe, tried to negotiate an end to the protest. Roosevelt arranged for his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, to visit the site unaccompanied. She lunched with the veterans and listened to them perform songs. She reminisced about her memories of seeing troops off to World War I and welcoming them home. The most that she could offer was a promise of positions in the newly created Civilian Conservation Corps.[45] One veteran commented, "Hoover sent the army, Roosevelt sent his wife."[49] In a press conference following her visit, the First Lady described her reception as courteous and praised the marchers, highlighting how comfortable she felt despite critics of the marchers who described them as communists and criminals.[45]

On May 11, 1933,[50] Roosevelt issued an executive order allowing the enrollment of 25,000 veterans in the CCC, exempting them from the normal requirement that applicants be unmarried and under the age of 25.[51] Congress, with Democrats holding majorities in both houses, passed the Adjusted Compensation Payment Act in 1936, authorizing the immediate payment of the $2 billion in World War I bonuses, and then overrode Roosevelt's veto of the measure.[52] The House vote was 324 to 61,[53] and the Senate vote was 76 to 19.[54]

In literature

[edit]The shootings are depicted in Barbara Kingsolver's novel The Lacuna.[55]

The Bonus Marchers are detailed in John Ross's novel Unintended Consequences (novel).

A fictionalized version of the Bonus March is depicted in the opening scenes of the 1995 movie In Pursuit of Honor.

The main character of Neal Stephenson's 2024 novel, Polostan (novel) travels with a group of communists within the bonus army to Washington, and is embroiled the army intervention.

See also

[edit]- Coxey's Army

- Fry's Army

- List of rallies and protest marches in Washington, D.C.

- List of incidents of political violence in Washington, D.C.

- On-to-Ottawa Trek by Canadian veterans, 1935

- Social history of soldiers and veterans in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Heroes: Battle of Washington". Time. August 8, 1932. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

Last week William Hushka's Bonus for $528 suddenly became payable in full when a police bullet drilled him dead in the worst public disorder the capital has known in years.

- ^ "'Take Job in the Forest or Go Home' Is Alternative Given to Bonus Boys", Middlesboro (Kentucky) Daily News, May 17, 1933, p. 1; "Bonus Marchers Weaken; Accept Jobs in Ax Corps", Milwaukee Journal, May 20, 1933, p. 1

- ^ Graves, Will. "Pension Acts An Overview of Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Legislation and the Southern Campaigns Pension Transcription Project". Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ "Education and Training". History and Timeline. November 21, 2013. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ David Greenberg, Calvin Coolidge (NY: Henry Holt, 2006), 78–79

- ^ Greenberg, David (2006). Calvin Coolidge: The American Presidents Series. Times Books. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0805069570.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Dickson and Allen, 29

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Dickson and Allen, 37–38

- ^ Dickson and Allen, 34

- ^ Stephen R. Ortiz, "The 'New Deal' for Veterans: The Economy Act, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and the Origins of the New Deal," Journal of Military History, vol. 70 (2006), 434–45

- ^ Dickson and Allen, 49–50.

- ^ "The Last Time the U.S. Army Cleared Demonstrators From Pennsylvania Avenue". Politico.com. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ "HEROES: Battle of Washington". Time. August 8, 1932. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Daniels, Roger (1971). The Bonus March: An Episode of the Great Depression. Praeger. p. 106. ISBN 0837151740.

- ^ Dickson, Paul (2020). The Bonus Army: An American Epic. Thomas B. Allen. [S.l.]: Dover Publications. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0486848358. OCLC 1201836137.

- ^ "The Bonus Army". Eyewitnesstohistory.com. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Bartlett, John H. (1937). The Bonus March and the New Deal. Chicago: M.A. Donohue & Company. p. 105. OCLC 477820.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (2009). "House passes bonus bill for WWI veterans, June 15, 1932". Politico. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ Staff Correspondent (June 18, 1932). "Senate Defeats Bonus Despite 10,000 Veterans Massed Around Capitol". The New York Times. No. 27, 174. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

{{cite news}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ "Veteran dies of wounds". The New York Times. August 2, 1932. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Hushka, William. "William Hushka". Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. View original photograph. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Hushka, William. "William Hushka". Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. View original photograph. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Mentioned in "The March of the Bonus Army" video, 30 min. Retrieved from answer.com 2011-2-4.

- ^ "Bonus Army Spectacle, U.S. Capital, 1932: What Really Happened. Section VI. Two Shootings at Glassford Camp". Suburban Emergency Management Project (SEMP), Biot Report #635. July 18, 2009. Archived from the original on July 30, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ "Bonus Expeditionary Force Martyrs Hushka & Carlson (1932)". DC Labor Map. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ "The Bonus Army". Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Lisio, Donald J. “A Blunder Becomes Catastrophe: Hoover, the Legion, and the Bonus Army.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 51, no. 1, 1967, p. 40 JSTOR 4634286

- ^ a b Statement on the Justice Department Investigation of the Bonus Army (September 10, 1932). The American Presidency Project, UC Santa Barbara

- ^ Hoover, Herbert (1952, 2011). The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: The Great Depression, 1929–1941. Read Books, ISBN 1447402472, pp. 225–226

- ^ Gitlow, Benjamin (1948). The Whole of Their Lives: Communism in America—A Personal History and Intimate Portrayal of Its Leaders. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 226–230. ISBN 0836980948. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- ^ Craughwell, Thomas (January 16, 2009). "#6: Hoover's Attack on the Bonus Army (Top 10 Mistakes by U.S. Presidents)". Encyclopedia Britannica Blog. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- ^ Smith, Jean Edward (2012). Eisenhower in War and Peace. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 110–113. ISBN 978-0679644293.

- ^ Dickson and Allen, 176.

- ^ Dickson and Allen, 182–83

- ^ Dickson and Allen, 170–74, 180

- ^ Wukovits, John F. (2006). Eisenhower. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 43. ISBN 0230613942. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ D'Este, Carlo (2002). Eisenhower: A Soldier's Life. New York: Henry Holt & Co. p. 223. ISBN 0805056874. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Jean Edward (2012). Eisenhower in War and Peace. New York: Random House. pp. 109–113. ISBN 978-0679644293.

- ^ "FOR THE RECORD : From "My Search for Douglas MacArthur" by Geoffrey Perret in the February/March issue of American Heritage". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ "My Search For Douglas MacArthur". Americanheritage.com. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Hirshson, Stanley P. General Patton. Harper Collins Publishers 2002. New York.[page needed]

- ^ Kingseed, Wyatt (June 2004). "The 'Bonus Army' War in Washington". American History magazine. Retrieved January 31, 2018 – via Historynet.com.

- ^ a b c Blanche Wiesen Cook, Eleanor Roosevelt (NY: Viking, 1999), vol. 2, 44–46

- ^ "Governor Lays Plans for Trip". The New York Times. October 17, 1932. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ "New Bonus March Starts Tomorrow" (PDF). The New York Times. May 9, 1933. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- ^ Staff Correspondent (May 15, 1933). "Bonus Army Row Finally Adjusted". The New York Times. No. LXXXII 27, 505. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

{{cite news}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ Jenkins 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Salmond, John A. (1967). "The CCC Is Mobilized". The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933–1942. Duke University Press.

- ^ Brands, H. W. (2009). Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 391. ISBN 978-0307277947.

- ^ "Bonus Bill Becomes Law". The New York Times. January 28, 1936. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ "House Swiftly Overrides Bonus Veto by Roosevelt". The New York Times. January 25, 1936. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ "Bonus Bill Becomes Law". The New York Times. January 28, 1936. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ Pohrt, Karl (November 12, 2009). "Barbara Kingsolver's". AnnArbor.com. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Bennett, Michael J. (1999). When Dreams Come True: The GI Bill and the Making of Modern America ISBN 157488218X online

- Burner, David. (1979). Herbert Hoover: A Public Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0394461347. online

- Daniels, Roger. (1971). The Bonus March: An Episode of the Great Depression. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0837151740, a major scholarly study; online

- Dickson, Paul, and Thomas B. Allen. (2004). The Bonus Army: An American Epic. New York: Walker and Company. ISBN 0802714404.

- Dickson, Paul, and Thomas B. Allen. "Marching On History," in Smithsonian, February 2003

- James, D. Clayton. (1970). The Years of MacArthur, Volume I, 1880–1941. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 36211265

- Jenkins, Roy (2003). Franklin Delano Roosevelt. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0805069594.

- Laurie, Clayton D. and Ronald H. Cole. (1997). The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1877–1945. Washington, DC: Center of Military History

- Liebovich, Louis W. (1994). Bylines in Despair: Herbert Hoover, the Great Depression, and the U.S. News Media ISBN 0275948439 online

- Lisio, Donald J. (1974). The President and Protest: Hoover, Conspiracy, and the Bonus Riot. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 082620158X

https://books.google.com/books?id=tSwSAAAAYAAJ&q=%27%27The+President+and+Protest:+Hoover,+Conspiracy,+and+the+Bonus+Riot%27%27.&dq=%27%27The+President+and+Protest:+Hoover,+Conspiracy,+and+the+Bonus+Riot%27%27.&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiG3vDCu-qJAxVJkIkEHSb_AvcQ6AF6BAgEEAI online]

- Perret, Geoffrey (1996). "MacArthur and the Marchers" in MHQ: the Quarterly Journal of Military History. Vol 8, No 2

- Smith, Richard Norton. (1984). An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 067146034X. online

Further reading

[edit]- Morrow, Felix. (1932). The Bonus March. International Pamphlets No. 31. New York: International Publishers. OCLC 12546840, a far-left perspective.

- Ortiz, Stephen R. 2006. "Rethinking the Bonus March: Federal Bonus Policy, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and the Origins of a Protest Movement". Journal of Policy History. 18, no. 3: 275–303. online

- Parker, Robert V. (1974) "The Bonus March of 1932: A Unique Experience in North Carolina Political and Social Life." North Carolina Historical Review 51.1 (1974): 64-89. ONLINE

- Rawl, Michael J. (2006). Anacostia Flats. Baltimore: Publish America. ISBN 978-1413797787.

- Smith, Gene. (1970). The Shattered Dream: Herbert Hoover and the Great Depression. New York: William Morrow and Company. OCLC 76078

- Tugwell, Rexford G. "Roosevelt and the Bonus Marchers of 1932." Political Science Quarterly 87.3 (1972): 363-376. Tugwell was a top FDR aide. online

- Vivian, James F., and Jean H. Vivian. "The Bonus March of 1932: The Role of General George Van Horn Moseley." Wisconsin Magazine of History (1967): 26-36. online

External links

[edit]- Sheilah Kast (February 13, 2005). "Soldier Against Soldier: The Story of the Bonus Army". NPR: Weekend Edition Sunday.

- The Bonus Army (EyeWitness to History)

- Vets Owe Debt to WWI's "Bonus Army from military.com

- FBI file on the Bonus Army

- The Sad Tale of the Bonus Marchers

- Memory: The Bonus Army March, Library of Congress

- Paul Dickson & Thomas B. Allen on The Bonus Army: An American Epic, a lecture recorded at the Pritzker Military Museum & Library

- 1932 protests

- 1932 in Washington, D.C.

- Aftermath of World War I in the United States

- Conflicts in 1932

- Great Depression in the United States

- History of veterans' affairs in the United States

- Police brutality in the United States

- Protest marches in Washington, D.C.

- Presidency of Herbert Hoover

- Military history of Washington, D.C.

- Douglas MacArthur

- George S. Patton

- July 1932 events

- 1932 United States presidential election

- Attacks on buildings and structures in Washington, D.C.

- Attacks on buildings and structures in the 1930s

- United States military scandals