P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1

| SELPLG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | SELPLG, CD162, CLA, PSGL-1, PSGL1, selectin P ligand | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

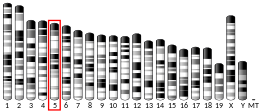

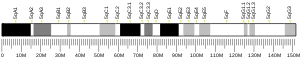

| External IDs | OMIM: 600738; MGI: 106689; HomoloGene: 2261; GeneCards: SELPLG; OMA:SELPLG - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

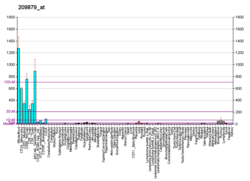

Selectin P ligand, also known as SELPLG or CD162 (cluster of differentiation 162), is a human gene.

SELPLG codes for PSGL-1, the high affinity counter-receptor for P-selectin on myeloid cells and stimulated T lymphocytes. As such, it plays a critical role in the tethering of these cells to activated platelets or endothelia expressing P-selectin. The gene and structure of human PSGL-1 was first reported in 1993.[5]

The organization of the SELPLG gene closely resembles that of CD43 and the human platelet glycoprotein GpIb-alpha both of which have an intron in the 5-prime-noncoding region, a long second exon containing the complete coding region, and TATA-less promoters.[6]

P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) is a glycoprotein found on white blood cells and endothelial cells that binds to P-selectin (P stands for platelet), which is one of a family of selectins that includes E-selectin (endothelial) and L-selectin (leukocyte). Selectins are part of the broader family of cell adhesion molecules. PSGL-1 can bind to all three members of the family but binds best (with the highest affinity) to P-selectin.

Posttranslational modification

[edit]PSGL-1 protein requires two distinct posttranslational modifications to gain its selectin binding activity:[7][8][9][10]

- sulfation of tyrosines

- the addition of the sialyl Lewis x tetrasaccharide (sLex) to its O-linked glycans

Function

[edit]PSGL-1 is expressed on all white blood cells and plays an important role in the recruitment of white blood cells into inflamed tissue: White blood cells normally do not interact with the endothelium of blood vessels. However, inflammation causes the expression of cell adhesion molecules (CAM) such as P-selectin on the surface of the blood vessel wall. White blood cells present in flowing blood can interact with CAM. The first step in this interaction process is carried out by PSGL-1 interacting with P-selectin and/or E-selectin on endothelial cells and adherent platelets. This interaction results in "rolling" of the white blood cell on the endothelial cell surface followed by stable adhesion and transmigration of the white blood cell into the inflamed tissue.[citation needed]

Clinical significance

[edit]In inflammation

[edit]The systemic administration of soluble recombinant forms of human PSGL-1 such as rPSGL-Ig or TSGL-Ig can prevent reperfusion injury caused by leukocyte influx after an ischemic insult to various types of vascularized tissues (IRI). The protective effects of soluble recombinant forms of PSGL-1, acting as pan-selectin antagonists, has been studied in multiple animal models of solid organ transplant and ARDS.[11][12]

In cancer

[edit]In mice it seems to be an immune factor regulating T-cell checkpoints, and it could be a target for future checkpoint inhibitor anti-cancer drugs.[13]

PSGL-1 has been shown to bind to VISTA (V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation) but this binding only occurs under acidic pH conditions (pH < 6.5) such as can be found in tumor microenvironments (TME).[14]

In mice, PSGL-1 seems to facilitate T cell exhaustion in tumors.[15] Treatments with monoclonal antibodies binding to PSGL-1 reduce tumor growth in mouse models, especially when combined with anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody treatments.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000110876 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000048163 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Sako D, Chang XJ, Barone KM, Vachino G, White HM, Shaw G, et al. (December 1993). "Expression cloning of a functional glycoprotein ligand for P-selectin". Cell. 75 (6): 1179–1186. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90327-m. PMID 7505206.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: SELPLG selectin P ligand".

- ^ Li F, Wilkins PP, Crawley S, et al. (1996). "Post-translational modifications of recombinant P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 required for binding to P- and E-selectin". J. Biol. Chem. 271 (6): 3255–64. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.6.3255. PMID 8621728.

- ^ Wilkins PP, Moore KL, McEver RP, Cummings RD (1995). "Tyrosine sulfation of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is required for high affinity binding to P-selectin". J. Biol. Chem. 270 (39): 22677–80. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.39.22677. PMID 7559387.

- ^ Sako D, Comess KM, Barone KM, et al. (1995). "A sulfated peptide segment at the amino terminus of PSGL-1 is critical for P-selectin binding". Cell. 83 (2): 323–31. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90173-6. PMID 7585949. S2CID 65420.

- ^ Pouyani T, Seed B (1995). "PSGL-1 recognition of P-selectin is controlled by a tyrosine sulfation consensus at the PSGL-1 amino terminus". Cell. 83 (2): 333–43. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90174-4. PMID 7585950. S2CID 17480260.

- ^ Zhang C, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Liu Y, Kageyama S, Shen XD, et al. (June 2017). "A Soluble Form of P Selectin Glycoprotein Ligand 1 Requires Signaling by Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 to Protect Liver Transplant Endothelial Cells Against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury". American Journal of Transplantation. 17 (6): 1462–1475. doi:10.1111/ajt.14159. PMC 5444987. PMID 27977895.

- ^ Sun X, Sammani S, Hufford M, Sun BL, Kempf CL, Camp SM, et al. (January 2023). "Targeting SELPLG/P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 in preclinical ARDS: Genetic and epigenetic regulation of the SELPLG promoter". Pulmonary Circulation. 13 (1): e12206. doi:10.1002/pul2.12206. PMC 9982077. PMID 36873461.

- ^ Tinoco R, Carrette F, Barraza ML, Otero DC, Magaña J, Bosenberg MW, et al. (May 2016). "PSGL-1 Is an Immune Checkpoint Regulator that Promotes T Cell Exhaustion". Immunity. 44 (5): 1190–203. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.015. PMID 27192578.; Lay summary in: Kegel M (1 June 2016). "Immune Factor Seen to Control T-Cell Checkpoints Involved in Spread of Cancers and Infections". Immune-onocology News.

- ^ Johnston RJ, Su LJ, Pinckney J, Critton D, Boyer E, Krishnakumar A, et al. (October 2019). "VISTA is an acidic pH-selective ligand for PSGL-1". Nature. 574 (7779): 565–570. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1674-5. PMID 31645726.

- ^ Hope JL, Otero DC, Bae EA, Stairiker CJ, Palete AB, Faso HA, et al. (May 2023). "PSGL-1 attenuates early TCR signaling to suppress CD8+ T-cell progenitor differentiation and elicit terminal CD8+ Tcell exhaustion". Cell Reports. 42 (5): 112436. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112436. PMID 37115668.; Lay summary in: Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (4 May 2023). "Reviving exhausted T cells to tackle immunotherapy-resistant cancers". Medical Press.

- ^ Novobrantseva T, Manfra D, Ritter J, Razlog M, O'Nuallain B, Zafari M, et al. (August 2024). "Preclinical Efficacy of VTX-0811: A Humanized First-in-Class PSGL-1 mAb Targeting TAMs to Suppress Tumor Growth". Cancers. 16 (16): 2778. doi:10.3390/cancers16162778. PMC 11352552. PMID 39199551.

Further reading

[edit]- Furie B, Furie BC (April 2004). "Role of platelet P-selectin and microparticle PSGL-1 in thrombus formation". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 10 (4): 171–178. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2004.02.008. PMID 15059608.

- Sako D, Chang XJ, Barone KM, Vachino G, White HM, Shaw G, et al. (December 1993). "Expression cloning of a functional glycoprotein ligand for P-selectin". Cell. 75 (6): 1179–1186. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90327-M. PMID 7505206. S2CID 23786141.

- Moore KL, Eaton SF, Lyons DE, Lichenstein HS, Cummings RD, McEver RP (September 1994). "The P-selectin glycoprotein ligand from human neutrophils displays sialylated, fucosylated, O-linked poly-N-acetyllactosamine". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (37): 23318–23327. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)31656-3. PMID 7521878.

- Veldman GM, Bean KM, Cumming DA, Eddy RL, Sait SN, Shows TB (July 1995). "Genomic organization and chromosomal localization of the gene encoding human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (27): 16470–16475. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.27.16470. PMID 7541799.

- Maruyama K, Sugano S (January 1994). "Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides". Gene. 138 (1–2): 171–174. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90802-8. PMID 8125298.

- Guyer DA, Moore KL, Lynam EB, Schammel CM, Rogelj S, McEver RP, et al. (October 1996). "P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) is a ligand for L-selectin in neutrophil aggregation". Blood. 88 (7): 2415–2421. doi:10.1182/blood.V88.7.2415.bloodjournal8872415. PMID 8839831.

- Goetz DJ, Greif DM, Ding H, Camphausen RT, Howes S, Comess KM, et al. (April 1997). "Isolated P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 dynamic adhesion to P- and E-selectin". The Journal of Cell Biology. 137 (2): 509–519. doi:10.1083/jcb.137.2.509. PMC 2139768. PMID 9128259.

- Fuhlbrigge RC, Kieffer JD, Armerding D, Kupper TS (October 1997). "Cutaneous lymphocyte antigen is a specialized form of PSGL-1 expressed on skin-homing T cells". Nature. 389 (6654): 978–981. Bibcode:1997Natur.389..978F. doi:10.1038/40166. PMID 9353122. S2CID 4376296.

- Suzuki Y, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Maruyama K, Suyama A, Sugano S (October 1997). "Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5'-end-enriched cDNA library". Gene. 200 (1–2): 149–156. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00411-3. PMID 9373149.

- Snapp KR, Ding H, Atkins K, Warnke R, Luscinskas FW, Kansas GS (January 1998). "A novel P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 monoclonal antibody recognizes an epitope within the tyrosine sulfate motif of human PSGL-1 and blocks recognition of both P- and L-selectin". Blood. 91 (1): 154–164. doi:10.1182/blood.V91.1.154. PMID 9414280.

- Bennett EP, Hassan H, Mandel U, Mirgorodskaya E, Roepstorff P, Burchell J, et al. (November 1998). "Cloning of a human UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-Galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase that complements other GalNAc-transferases in complete O-glycosylation of the MUC1 tandem repeat". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (46): 30472–30481. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.46.30472. hdl:2066/216411. PMID 9804815.

- Wimazal F, Ghannadan M, Müller MR, End A, Willheim M, Meidlinger P, et al. (November 1999). "Expression of homing receptors and related molecules on human mast cells and basophils: a comparative analysis using multi-color flow cytometry and toluidine blue/immunofluorescence staining techniques". Tissue Antigens. 54 (5): 499–507. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.1999.540507.x. PMID 10599889.

- Epperson TK, Patel KD, McEver RP, Cummings RD (March 2000). "Noncovalent association of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 and minimal determinants for binding to P-selectin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (11): 7839–7853. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.11.7839. PMID 10713099.

- André P, Spertini O, Guia S, Rihet P, Dignat-George F, Brailly H, et al. (March 2000). "Modification of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 with a natural killer cell-restricted sulfated lactosamine creates an alternate ligand for L-selectin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (7): 3400–3405. doi:10.1073/pnas.040569797. PMC 16251. PMID 10725346.

- Frenette PS, Denis CV, Weiss L, Jurk K, Subbarao S, Kehrel B, et al. (April 2000). "P-Selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1) is expressed on platelets and can mediate platelet-endothelial interactions in vivo". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 191 (8): 1413–1422. doi:10.1084/jem.191.8.1413. PMC 2193129. PMID 10770806.

- Woltmann G, McNulty CA, Dewson G, Symon FA, Wardlaw AJ (May 2000). "Interleukin-13 induces PSGL-1/P-selectin-dependent adhesion of eosinophils, but not neutrophils, to human umbilical vein endothelial cells under flow". Blood. 95 (10): 3146–3152. doi:10.1182/blood.V95.10.3146. PMID 10807781.

- Tsuchihashi S, Fondevila C, Shaw GD, Lorenz M, Marquette K, Benard S, et al. (January 2006). "Molecular characterization of rat leukocyte P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 and effect of its blockade: protection from ischemia-reperfusion injury in liver transplantation". Journal of Immunology. 176 (1): 616–624. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.616. PMID 16365457.

External links

[edit]- P-selectin+glycoprotein+ligand-1 at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.